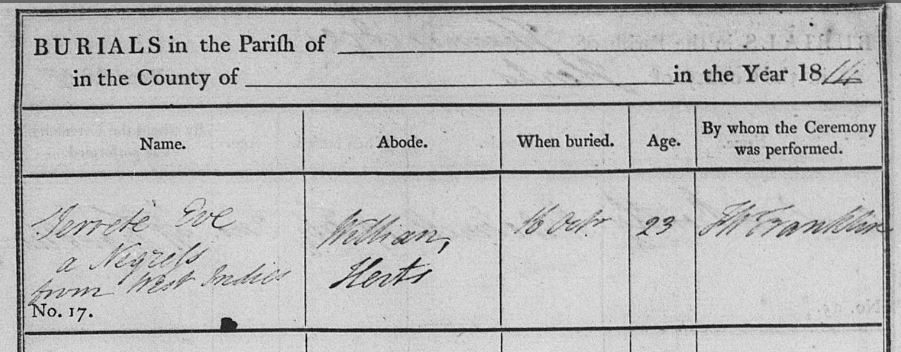

The burial of Jeanette Eve of Willian, near Hitchin, 23, was registered at Thundridge [Old] Church on the 16th October 1814.

Like her more famous French contemporary Madeleine, whose portrait (left) was formally known as ‘Portrait of a Negress’, little is known about Eve’s life. Both women were of West Indian extraction. As residents in countries where slavery was not authorised, Madeleine and Jeanette may have been servants or freewomen, perhaps living under the protection of benefactors or families who had run or owned plantations in the West Indies.

Madeleine is thought to have come to France from French owned Guadalupe, where the French Revolutionary Government had banned slavery in 1794. Her portrait is said to be an allegory for revolution and freedom, as she is fashionably, albeit partially, clothed in blue, white and red, like the Marianne of the Revolution era. The politically charged depiction of Madeleine was a controversial subject for its painter. Marie-Guillemine Laville-Leroulx had been raised to earn her own living as a painter and along with her sister was working in the Louvre studio of Revolution-supporting artist Jacque-Louis David, before her marriage in 1793 to Pierre- Vincent Benoist, a monarchist who supported Napoleon Bonaparte’s intention in 1800 to revive slavery in the French Colonies for economic gain, and which was reinstated in 1802.

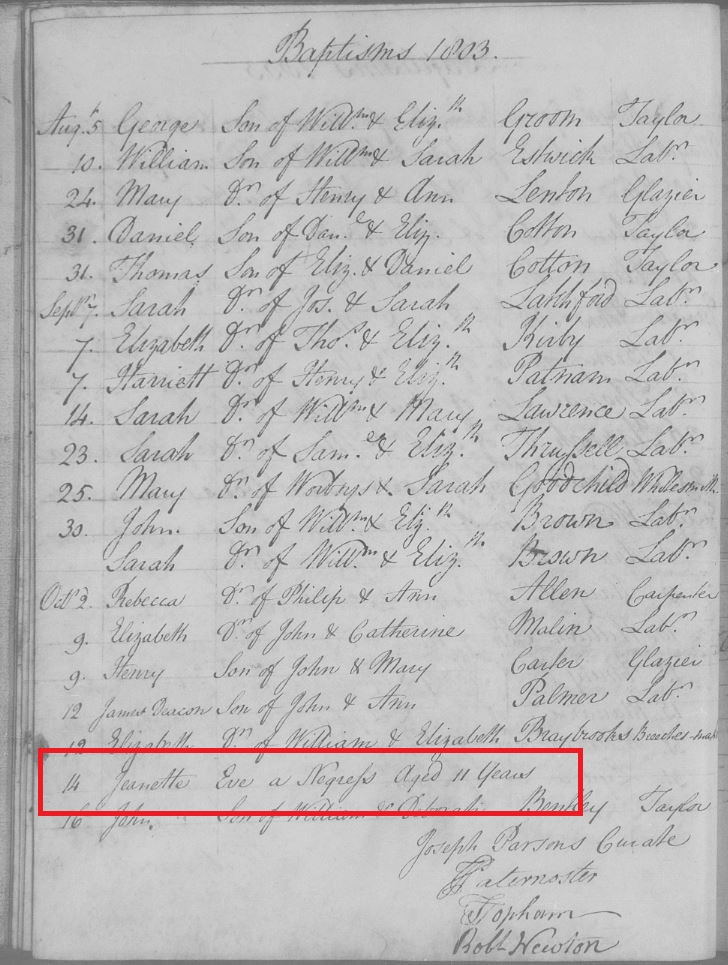

Jeanette was christened at St Mary’s Hitchin on 14th October 1803, age 11, probably by curate Joseph Parsons, newly arrived from Essex. Hitchin’s Rector, Rev John Rippon MA, had connections with royalty, and was appointed domestic chaplain in January 1804 to Anne (née Luttrell later Horton), widow of the late Duke of Cumberland, whose decadent Brighthelmstone [Brighton] lifestyle and 1771 marriage to Prince Henry as a widowed commoner led to his brother King George III’s Royal Marriages Act of 1772.

Jeanette was christened at St Mary’s Hitchin on 14th October 1803, age 11, probably by curate Joseph Parsons, newly arrived from Essex. Hitchin’s Rector, Rev John Rippon MA, had connections with royalty, and was appointed domestic chaplain in January 1804 to Anne (née Luttrell later Horton), widow of the late Duke of Cumberland, whose decadent Brighthelmstone [Brighton] lifestyle and 1771 marriage to Prince Henry as a widowed commoner led to his brother King George III’s Royal Marriages Act of 1772.

Jeanette Eve’s relations in Hitchin are not recorded. Non conformist records include the family of Richard Eve of Tile House Baptist Church Hitchin, whose grandson Henry Weston Eve (1838-1910) would become headmaster of University College School, London. Another Henry Eve was christened at Letchworth Church in 1794, son of Mary and Henry Eve of Berners [pronounced Barnish] Roding, Essex [the family seat they returned to in 1794], who had leased Letchworth Farm from the Lyttons of Knebworth in 1780; the younger Henry Eve was later appointed Rector of South Ockendon, Essex.

The surname ’Eve’ might indicate servitude with a gentry estate: Hunsdon registers record that Africk Hunsdon was a servant (by 1711) to Matthew Blucke of Hunsdon House; and Peter Gordon served (by 1786) Lord Adam Gordon (son of the Duke of Gordon) previously of Copt Hall, Hunsdon.

‘Eve’ could suggest residency, descent and/or property of a plantation: rent books record that a William Eve owned 153 acres in Vere (west of Kingston) Jamaica in 1754; an Eve family were compensated over £27 in 1836 for the emancipation of 5 slaves on their plantations in Bermuda. Eve is also a possible transcription for an entry in The Book of Negroes, compiled in 1783 by Brig General Samuel Birch to name and describe 3,000 Black Loyalists, enslaved Africans who fled to British lines during the American Revolution and were evacuated to Nova Scotia. Other Black Loyalists were transported to West Indian islands and London. Some of these displaced peoples were later relocated to Freetown, Sierra Leone, in 1792 by Thomas Clarkson’s brother Lieutenant John Clarkson Royal Navy for the Sierra Leone Company. The ‘Province of Freedom’ in Sierra Leone had first been settled, unsuccessfully, as Granville Town in 1787 by 400 formerly enslaved black people sent from London, England, by British Abolitionist Granville Sharp’s Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor.

Jeanette was buried at Thundridge on the 16th October 1814, however her connections to Thundridge remain an enigma.

Jeanette was buried at Thundridge on the 16th October 1814, however her connections to Thundridge remain an enigma.

Elizabeth (née Rumble) and John Eve, both of Thundridge parish, were married by Rev John White at Thundridge on 6th November 1777, and their son George was christened at Thundridge a year later, but no relationship to Jeanette is known. The reference to Jeanette’s West Indian heritage is unique in the Thundridge church records, although skin colour was noted elsewhere, eg Standon’s 1806 burial record of Puckeridge’s George Mitchell, 48.

Jeanette was said to be 11 when christened in Hitchin (14/10/1803) and 23 when buried at Thundridge (16/10/1814), so her birthday might be the 15th October 1791; or perhaps she did not know her true age. No record of Jeanette Eve’s birthplace has been found; no transcriptions of the grave stones and boards at Thundridge mention her name

From 1791, Ware and Thundridge was a second living for Rev Henry Allen Lagden, who resided at Weston Colville Rectory, Cambridgeshire. By 1811, Thundridge parish’s curate was Rev Frederick Franklin (no known relation to previous vicar and playwriter Rev Thomas Francklin). Educated at Christ’s Hospital School then Cambridge, Franklin had been assistant master at Christ’s Hospital for a decade when he officiated at Jeanette’s funeral

Thundridge parish’s association with slavery abolition had been noted for decades by 1814. 29 years earlier Thomas Clarkson, 23, had stopped on Wadesmill Hill, near the gates to David Barclay’s Youngsbury Estate, to reflect on his prize winning essay, ’Is it lawful to make slaves of others against their will?’

On returning [from Cambridge] to London, the subject of it almost wholly engrossed my thoughts. I became at times very seriously affected while upon the road. I stopped my horse occasionally, and dismounted and walked. I frequently tried to persuade myself in these intervals that the contents of my Essay could not be true. The more however I reflected upon them, or rather upon the authorities on which they were founded, the more I gave them credit. Coming in sight of Wades Mill in Hertfordshire, I sat down disconsolate on the turf by the roadside and held my horse. Here a thought came into my mind, that if the contents of the Essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to their end. Agitated in this manner I reached home. This was in the summer of 1785. Thomas Clarkson

In 1788 Rev William Hughes, Vicar of Ware and Thundridge, was made an honorary member of The Society for the Abolition of Slavery, for speaking out against arguments that Christian texts condoned slavery. Hughes probably knew Josiah Wedgewood who had produced and distributed the anti-slavery medallion featuring a kneeling enslaved man in chains and the phrase ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’ from 1787. Hughes’ distant cousin ‘Bessie’ Allen of Cresselly, Pembrokeshire, married Joshua Wedgewood jnr in 1792.

Rev Hughes, 45, died at Thundridge Vicarage on November 7th 1790, he was laid to rest near the north wall of Thundridge churchyard; the wall has since collapsed over the site. In contrast, the Thomas Clarkson Memorial, installed in 1879 by the Giles-Puller family of Youngsbury, at the site of his Wadesmill epiphany in 1785, has been renovated at least three times,

Quaker Abolitionist David Barclay, previously of Youngsbury, and his late brother John had received the 2000 acre Unity Valley Pen [grazing property] in Jamaica, and a mortgage secured on Yorkshire Hall Plantation, Barbados, as mercantile debts. In 1795 David re-settled 16 freed adults and 12 children, from Unity Valley to Philadelphia. David gave up his intention to trial employing white British labourers at Unity Valley; sold the property’s stock of cattle; resettled four further persons for life in Jamaica; and secured apprenticeships for those in Philadelphia. This was done at a personal expense of £13000.