Around 6,000 moated sites are known in England. They consist of wide ditches, often or seasonally water-filled, partly or completely enclosing one or more islands of dry ground on which stood domestic or religious buildings. In some cases the islands were used for horticulture. The majority of moated sites served as prestigious aristocratic and seigneurial residences with the provision of a moat intended as a status symbol rather than a practical military defence. The peak period during which moated sites were built was between about 1250 and 1350 and by far the greatest concentration lies in central and eastern parts of England. However, moated sites were built throughout the medieval period, are widely scattered throughout England and exhibit a high level of diversity in their forms and sizes. They form a significant class of medieval monument and are important for the understanding of the distribution of wealth and status in the countryside. Many examples provide conditions favourable to the survival of organic remains.

Thundridgebury moated enclosure is unusual for its extensive size, covering up to 2.8ha, and for the range of features it surrounds. It is “D” shaped with external dimensions of approximately 195m north-south by 200m east-west. The surrounding dry moat varies in width between 7m and 20m, but part of the southern arm and the south-east corner is obscured. Three causewayed breaks in the northern arm of the moat are thought to be modern.

The interior of the enclosure, now in the wooded area to the North of the churchyard, contains the ruined remains of Thundridgebury House, believed to date from the 16th century. A series of brick foundations indicate the location of the house and outbuildings which were demolished in 1811. Immediately to the south of the house are the remains of St. Mary and All Saints’ Church.

The moated enclosure was scheduled in 1990 as Historic England List Entry Number 1012268, with the extents shown below

Before it’s partial demolition in 1853 ( see below) the church measured about 25m by 12m. The foundations can still be seen in drought marks, such as those shown below in 2020.

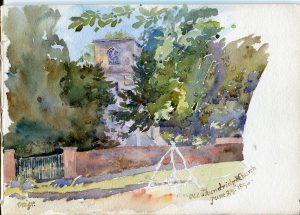

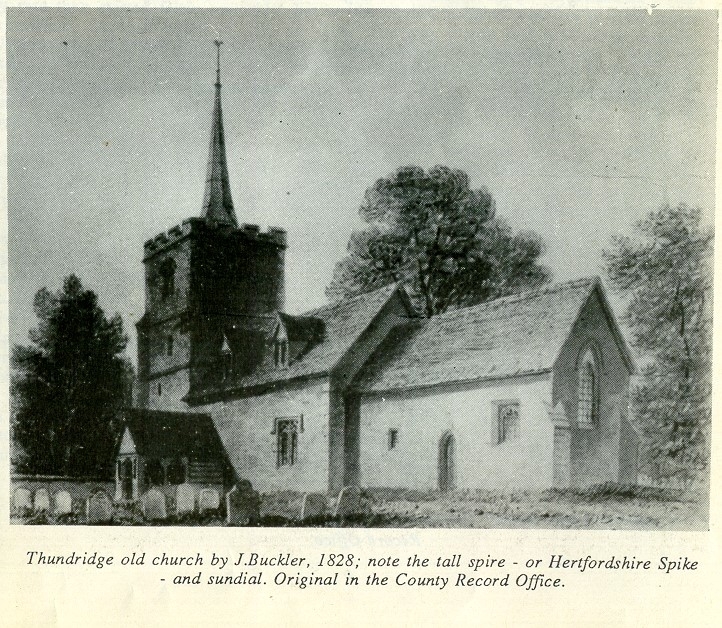

Several images of the church survive, shown below are an engraving by J Buckler in 1828 and a model that used to be in Hertford Museum, now lost.

The castellated 15C tower had a ‘Hertfordshire Spike’ on top

The nave was built of flint and rubble leading through the chancel arch to a tiled and plastered eastern chancel.

The porch just to the east of the tower led to a Norman door

Contrary to the lurid tales still being peddled by local newspapers and elsewhere, the church is demonstrably on a perfectly normal East-West alignment, with the main altar at the east end of the church, facing Jerusalem and not in the lazily ‘rumoured’ satanic North-South orientation.

Documents reference a Saxon chancel arch but there are no images of this or any other diagnostic Saxon features, so this remains speculative.

No archaeological investigation of the churchyard or moated enclosure has ever taken place, but Saxon churches were often located on pre-Christian sites of spiritual significance, taking advantage of people’s existing devotion to a particular place. The Rib Valley in this immediate area has flint artefacts back to the stone age, early Bronze Age ‘Beaker’ burials and ring ditch structures most likely funerary/ceremonial round barrows of the same era, Roman barrows (with artefacts in the Verulamium Museum at St Albans), and 6th century BC pottery, bones and honing stones for sharpening metal, indicating an Iron Age settlement. Prior to the current ‘Great North Road’/Roman Ermine Street, the church site is likely to have been on the location of the main North South artery, on an easier gradient and crossing point than Wadesmill Hill. In short, this location has had occupation and deep significance that has hardly begun to be fully investigated.

Thundridge was held by Alnoth, a man of Archbishop Stigand, before the Conquest, and by Hugh de Grandmesnil from Bishop Odo of Bayeux thereafter. When Odo forfeited his holdings after his arrest in 1082, the Grandmesnils continued to hold as tenants-in-chief from the king. By the 13thc the tenants under the Grandmesnils were the family of Dive of Balderton; William de Dive died before 1251, and John Dive was the lord in 1277 and at his death in 1292-93. The later history of the manor can be found in Victoria County History: Hertfordshire vol. 3 (1912), 377-80.

The church was originally a chapel of Ware, and both the mother church and Thundridge chapel were given to the Priory of Ware by Hugh de Grandmesnil

The manor of Thundridge is recorded in the Doomsday book. Called ‘Little St Mary’s’ due to its being linked to St Mary’s, Ware; it is said to have been the summer home of the Priors of Normandy’s St Evroul, parts of whose Priory was later absorbed into ‘The Manor House’ on Church Street, Ware.

During the Norman period in the 12th Century, an arch was added to frame the entrance to the church. When the nave was demolished, this finely carved chevron toothed semicircular arch with billet mouldings was relocated into the blocked up tower arch where it still remains. This arch can be seen in it’s original position below in an ink and watercolour sketch entitled ‘Entrance to Thundridge Church’ dated 21st April 1845

By 1229, the congregation at Little St Mary’s and All Hallows’ was sufficient for the Prior of Ware to grant Thundridge’s own chaplain a decent house, four acres of land and a penny every Sunday.

The window above the Norman door dates to the 14th Century. Like the door, it was moved into the blocking of the tower arch when the nave was demolished.

It is described as a ‘2- light square headed, ogee traceried window with ferramenta and label with carved headstops, in blocking of equilateral C15 tower arch with hollow moulded imposts’

This window, like that in the west tower, is currently secured behind protective coverings

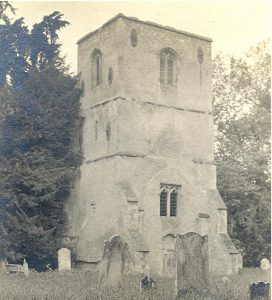

The west tower itself was built in the 15th century. It is constructed of flint rubble with stone dressings and angled (diagonal) buttresses on the two west corners and has three stages (stories), although no floors or structures remain inside – it is just an empty space from floor to roof, partially filled at floor level with rubble to discourage break-ins and further vandalism damage. Inside the tower can still be seen the blank diamond (lozenge) shape where the the Royal Coat of Arms was displayed in all churches in the early 1800’s. This was rehung at St Mary’s in 1892, and can still be seen there.

Inside on the southwest corner is a small spiral staircase leading up to what would have been the first floor. Outside on the same corner can be seen two very small openings which brought light into the staircase. One has been photographed with a resident owl.

At the very top of the tower, as can clearly be seen in Bucklers illustration, there was an embattled parapet (i.e. battlements like a castle wall) and a lead-covered ‘Hertfordshire Spike’, half the tower’s height again with a weathervane and cock. All this is now gone, and the roof opening is closed by a concrete slab at former parapet level.

The West door is a ‘four-centered Tudor arch with depressed head’. That is a kind of arch that is low and wide with a slightly pointed apex. The ‘four centered’ description refers to how it is drafted geometrically. Above the arch is a ‘square head’ (surround). The area between the head and the arch, the spandrels, has some carved tracery. Around the outside of the square head is another layer of carving (moulding) , called a ‘label’, with ‘head-stops’ which are carved heads at the base of each short vertical drop. Only the right hand head is now discernable, and even that is badly worn. All the windows and door openings in the tower are carved from ‘clunch’ – a soft easily carved chalk limestone that sadly is easily weathered and vandalised.

Immediately above the West door is a window. This has the same fourcentred arch shape as the door below. Within the main arch are three ‘lights’ (openings) each with five ‘cinquefoiled’ petal mouldings at the top. There are no good pictures of this window, it has been covered throughout living memory.

The second stage of the tower has narrow single ‘slit’ windows on each of the north, south and west faces, with pointed arches. Inside these are surprisingly large window openings internally, something that looks like you could sit in comfortably.

Each face of the third and final stage, where the bells hung has windows, again under four centered arches, of two trefoiled lights (windows with two openings, each with three ‘petals’ at the top) with a quatrefoiled opening in the head, between each light at the very top.

On the South face, a 17th century sundial is engraved ‘Long Live the King’. The metal gnomon (the sticking out bit that casts the shadow) is rumoured to have been relocated to Fabdens, but this has not been corroborated.

Also on the South face is the Quatrefoil (see below)

In 1510, Thomas Gardiner of Wadesmill left ‘money for lights [windows] in church of “Allhaloen” in Thundridge.’ Dormer windows were added in the 1600’s.

For a considerable time the tower was heavily vandalised; gravestones, memorials, walls and railings were smashed and used to cause further damage, the tower itself was filled with rubbish and blacked by fire, and the site became a location for significant antisocial behaviour. This situation was, and potentially remains, a major risk in the long term future of the tower. In June 1990 the local authority served a Dangerous Structures notice on the Church tower and a series of escalating attempts were made to prevent vehicular access, seal the tower and remove loose material from the churchyard.

Happily, the measures taken since, including installing tree trunks and blocks on entrance paths, security frames and protective coverings on windows, filling the tower with rubble, maintaining the churchyard regularly, blocking doorways with reinforced concrete and installing sacrificial boards have for many years now hugely reduced, though sadly not completely eliminated the incidence of damage, given the site some much needed respite and returned to to being a welcoming place.

There is a natural curiosity to know what is inside the tower. In fact there is very little to see, the interior has no floors or structures and is heavily vandalised. As mentioned above, it is also now filled with rubble to a considerable depth, concealing the entrance to the spiral steps which are now inaccessible. Perhaps one day sufficient funding could be raised to be able to make the tower accessible again, but in the meantime some old photos are presented below.

On the South face of the tower is a carved panel clearly showing a quatrefoil shape inside a circle, with Plantagenet roses and fleur de Lys motifs, sketched in a watercolour (c.1800) by Henry George Oldfield

Of especial interest in this is the easily overlooked symbol towards the upper left of the surround. This is a Pelham buckle, and there were also three, now destroyed, carved into the West door.

The Pelham Buckle symbol was granted to John de Pelham, whose family had owned the manors of Pelham, Hertfordshire since before the Norman Conquest, in recognition of Pelham’s role in the capture of the French King Jean II at Poitiers in 1356. King Jean was imprisoned at Hertford Castle; and Thundridge and Ware’s monastic properties were seized from the alien St Evroul / Elbrulf Abbey (Normandy). William Blaauw, a noted local historian and Mark Anthony Lower, an authority on the ecclesiastical Pelham Buckles of Sussex, published articles that they considered the Thundridge Pelham Buckle to be the oldest of the Pelham monuments subsequently displayed on several Sussex church buildings endowed by Pelham’s son and his descendants.

Why the buckle allegedly appears here first and uniquely outside Sussex remains a mystery.

Six bells are associated with the Old Church, at least four of which still survive hanging in [New] St Mary’s Parish Church Thundridge. It is really exciting to know these artifacts still exist from some of the earliest history of the Old Church.

When Ware Priory was sacked in Henry VIII’s reign, the church was gifted to Trinity College, Cambridge.

“THE Rectory is impropriated to the perpetual Use of the Masters and Fellows of Trinity Colledge in Cambridgc; and this Vicaridge Anno 26 H.VIII. was rated in the King’s Books at the yearly Value of 6l [£6]. of which the Masters and Fellows aforesaid are the Patrons. This Church is dedicated to the Honour of the Virgin Mary, from whom it is called Little St. Maries, and is situated in the bottom of the Hill, near tile Mannor-house in the Deanery of Braughing, in the Diocess of London: The Chancel and Body of the Church are tyled, and at the West End of the Church is a square Tower, wherein are four small Bells, and a fair Shaft or Spire cover’d with Lead is erected upon the Tower.

Here lieth the Body of Roger Gardiner, elder Son of Edward Gardiner, Esq. and Martha his Wife, who departed this Life the 13th of April, 1658. Aged 21 Years and 9 Months:

Roger lies here before his Hour,

Thus doth the Gardiner lose his Flower.

Source: The Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire , Sir Henry CHAUNCY 1700

In 1841 the first steps began to be taken that would lead to the demolition of all but the tower and over the coming decades leaving the site very much as we see it today.

This part of the Church’s story continues here Demolition and Decline

The graveyard, (now “closed”) measures some 60m north-south by 40m east-west and contains numerous gravepits, many marked with stone headstones. Some of the graves are thought likely to date to the Medieval period, with further Medieval deposits preserved in the intervening areas.

In the last decades, many of the Old Church’s gravestones have deteriorated and are increasingly illegible. Three stones dating to the 1760’s were removed to the care of Ware museum and are still visible there

Thankfully the inscriptions have been surveyed and recorded by generations of historians including J E Cussans in 1870, W E Gerish in 1907, Alfred C Pagan in 1979 and the Thundridge and High Cross Society in 1993. In 2010, Hertfordshire Family History Society compiled these records to produce ‘Hertfordshire Monumental Inscriptions No 95; The Parish Churches of St Mary, Thundridge including St Mary, Thundridge Old Church and St John, High Cross’.

The crypt of the Old Church remains the resting place of members of the Gardiners of Thundridgebury. Three headstones show the impact of the pre-antibiotic era on child mortality; three girls died between November and Christmas Day 1802. However, the myth about ‘Cold Christmas Church’ being so named because of a mass grave of frozen children is doubly wrong. Firstly, church records contain no unusual patterns of numerous children dying at any time in history. In fact, Thundridge Parish’s death rate, even during plague years and during outbreaks of childhood diseases, was lower than that at Ware. There is also no evidence, physical or documented, of mass graves of any kind located in the churchyard. Secondly, this church was never called ‘Cold Christmas Church’, Cold Christmas simply being an unexceptional hamlet of a few dwellings a mile away.

The burial ground was enclosed by a 17th or 18th century brick wall, which stood 8 feet high until the late 1940’s, but now is largely cleared.